Marketing is everything.

For example, witness the well-documented phenomenon of many Americans despising Obamacare while still liking the Affordable Care Act (fyi: they are the same damn thing).

Or consider the worst branding decision of all time: “global warming.” As we all know, climate deniers just scoff and say, “Then why was it so cold this winter?” Such idiotic assertions are easier to dismiss with a new and improved term (i.e., “climate change”).

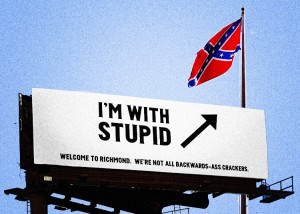

We are seeing the same pushback, the same dismissal of reality with the phrase “white privilege.” Now, for those who are unclear about this concept, white privilege refers to societal privileges that benefit white people beyond what is commonly experienced by non-white people. We can nitpick this definition, but that would be a whole other article.

The problem with white privilege is that the concept is painfully easy to refute. I’m not talking about right-wingers who insist that racism is dead or that white people are actually the disadvantaged class in America. There’s just no reaching those people.

No, I’m referring to white individuals who hear the word “privilege” thrown at them and interpret it as an individual attack rather than as a societal fact. Their reply is frequently, “There’s nothing privileged about my life.”

Indeed, as the wealth gap increases, plenty of white people are being left behind. And many of those struggling individuals come from ethnicities that endured their own struggles in the past (and occasionally, in the present). Under such circumstances, it’s galling — even ludicrous — to be told that you are privileged.

And what have good liberals done when confronted with this response? We stammer that privileges are often invisible, or that white people are less likely to be harassed by the cops, or that we’re not implying white people have had everything handed to them on a silver platter.

That’s all true of course. But it’s also true that if you’re explaining, you’re losing.

And that’s why we need to drop the whole thing — not the concept, mind you, which is crucial to our understanding of racial inequalities and American culture itself. We need to rebrand.

This has been pointed out before, but so far we have failed to come up with a good alternative.

So let’s begin the discussion in earnest. Let’s make it a real goal to replace the needlessly confrontational term “white privilege.”

I’ll get it started. How about “white advantage”? It’s still racially loaded, but the idea of “advantage” is much easier to accept than “privilege.”

Hey, just take it as a first draft. I’m sure working together, we can come up with something better.

Because we really need to.

More to the Story

Recently, I wrote about the dismal publishing scene for Latino authors. Well, I was remiss in at least one aspect. I implied that Hispanic writers are limited only to pitching the big New York publishing houses or jumping into the self-publishing quagmire. There is another option.

Namely, it is the world of small presses. Now, in the past, the phrase “small press” invoked images of ink-stained loners cranking out bizarre manifestos. Well, you’ll be glad to know those guys have moved on to troll internet comment pages across the web.

The small presses that exist today are often professionally run, highly principled organizations that focus on marginalized or experimental writers. And when it comes to Latino authors, we may be entering a golden age.

I’m talking about presses like Arte Publico, Floricanto, and Editorial Trance, all of which have been doing great work for years. And there is also Aignos Publishing, co-founded by Jonathan Marcantoni and Zachary Oliver.

Marcantoni says that Aignos, and other small presses that have a similar focus, look for writers who push boundaries and challenge readers to question their worldviews. Authors who embrace their distinct cultures — something Latino writers are well-known for doing — may find a home at Aignos or a similar small press.

“A small press gives authors the legitimacy of being affiliated with a company, one that is taken seriously by media and festivals and awards, in a way writers never get as self-published authors,” Marcantoni says. “Well-established small presses have marketing plans and publicists, plus the distribution channels are on par with what large presses use.”

Indeed, I can speak to this issue, as my own self-published novel, Barrio Imbroglio, is selling somewhere between hot cakes and lukewarm waffles.

It would certainly help to have an established marketing team behind me (my current marketing team consists of me and my cats).

Marcantoni says that when it comes to small presses, “the Latino author gets the best of both worlds: world-class distribution, a company backing their efforts, and creative freedom.”

That combo often leads to great books. For example, Aignos recently published Nuno, by Carlos Aleman. The novel is a lyrical love story set in pre-Castro Cuba and the aftermath of the revolution. Marcantoni says that Nuno doesn’t fit into mainstream expectations of Latino literature. As such, it lines up with Aignos’ mission of pushing writers to develop their views and skills instead of pressuring them to make the bestseller lists.

“No one should be a writer to be famous,” Marcantoni says. “It should come from a desire to express yourself and touch the lives of others.

So will we see more Hispanic authors telling their unique stories via small presses, touching the lives of more and more readers? Well, there’s ample reason to be optimistic about such a future.

“The Latino community can stand out as one of artists seeking to raise the bar of what storytelling can be,” Marcantoni says. “And there are publishers out there who will support you.”